Today’s long-overdue impeccable science is drawn from a pleasantly-sized 1832 volume entitled The Youth’s Book on Natural Theology; Illustrated in Familiar Dialogues, With Numerous Engravings.

For those who don’t know, natural theology argues for God’s existence based on observations of nature, so, while not a purely “scientific” tome by contemporary definitions, this book does contain highly-detailed descriptions of entomology, human anatomy, animal behavior, electricity, and air pressure, all of which the author relates to intelligent design.

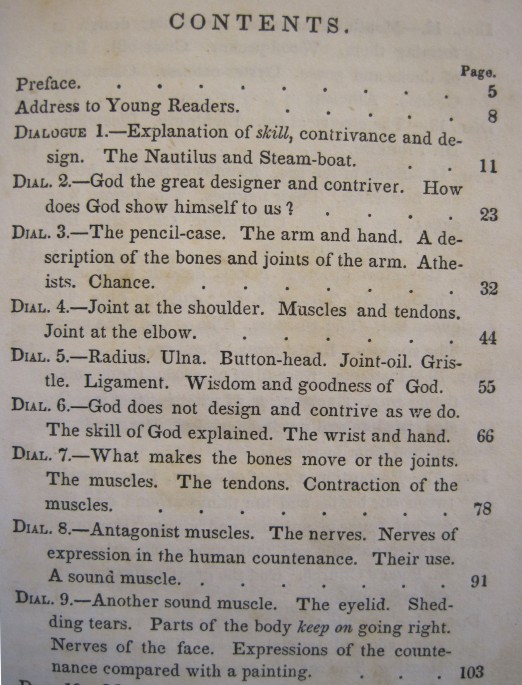

The chapter descriptions are truly brilliant litanies. My favorites are “Radius. Ulna. Button-head. Joint-oil. Gristle. Ligament. Wisdom and goodness of God.” and (not pictured here) “Mouth of animals; particular design in forming them. Wood-pecker. Cross-bill. Bills of ducks and geese. Oyster-catcher. Choetodon. Chance. Atheism.”

I will give an extremely special prize as well as certain micro-celebrity to any blog reader who can provide documentation of herself reciting these enumerations at a poetry reading.

As for the impeccable science that I’ve promised you: after a lengthy description of the nerves of the face and the ways that nerves control muscles, author Rev. T. H. Gallaudet proceeds to explain facial expressions, which “seem to be the very coming out of the soul.”

You, like me, may be thinking, “but I want my soul to stay in, where it belongs,” but that’s not what Rev. T. H. Gallaudet wants to talk about! No, he wants us to understand how uniquely human are facial expressions:

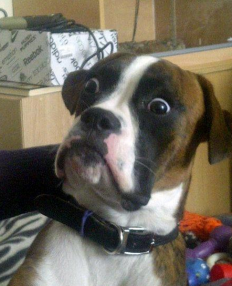

Many animals, you know, have no such expressions of face at all; and none of them have any thing like the different kinds,–the beauty, the strength, and the meaning, which the expressions of the human face have… a dog expresses a very few things by his face. A man can express,–oh! how many different kinds of thoughts, and feelings, in his countenance.

To which I say:

Gallaudet has proof, though! Just look at these lifelike engravings of a woman with soulful eyes and a disenchanted pup with Farrah Fawcett hair:

Why, you may ask, does that dog look so vacuous? In part, explains Gallaudet, it’s because animals don’t have souls, which I’m not prepared to debate here. In other part, it’s because:

Some [beasts] have some muscles and nerves, in their faces, like ours; but none of them as many; and most of them have very few, indeed… They do not think and feel, as we do… even, if they had a soul like ours, it could not show itself, its thoughts and its feelings, on their faces, as our souls do; because they have not the muscles and nerves, that are necessary to give all kinds of expressions to the face.

Hmmm. We may have to agree to disagree here, sir.

What about human facial expressions, though? What do those do, besides proving that we have souls?

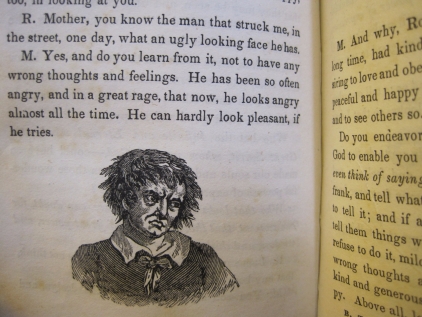

Well, they can show our habits of expression, which I think is an old-fashioned way of saying that if you make a funny face for too long, you’ll get stuck that way. For instance, look at this disheveled man who apparently strikes strange children in the street. He’s been angry for so long that “he can hardly look pleasant, if he tries”:

And here’s the same man after brushing his hair and putting on a less-floppy collar:

Just kidding! That’s a different man. That’s Uncle John, who’s full of kind and benevolent feelings. That’s why his eyebrows look so neat.

On a completely different note, I would be loathe to sign off without showing you this engraving–demonstrating the difference between instinct and behavior–of a woman frightening off a tiger with her parasol. It’s science! Impeccably!