I recently decided to take a look at one of the Benedict Arnold letters in our Updike Autograph Collection, and came across a curious situation. Here’s an image of the letter:

and the verso:

The letter is dated May 19th, 1775, just a month after the battles of Lexington and Concord, and it describes Benedict Arnold’s successful raid on Fort St. Jean in Quebec, where Arnold had captured a ship and the small group of soldiers at the fort. Here’s Arnold’s account from the letter:

Manned out two small batteaux with 35 men and at 6 the next morning arrived there and surprised a sergeant and his party of 12 men and took the King’s sloop of about 70 tons and 2 brass six-pounders and 7 men without any loss on either side. The captain was hourly expected from Montreal with a large detachment of men, some guns and carriages for the sloop, as was a captain and 40 men from Chambly at 12 miles distance from St. Johns, so that providence seems to have smiled on us in arriving so fortunate an hour. For had we been 6 hours later in all probability we should have miscarried in our design.

The letter is also notable for a passage in which Arnold describes an encounter with Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys:

I must here observe that in my return some distance this side [of] St. John I met Col. Allen with 90 or 100 of his men in a starving condition. I supplied him with provisions. He informed me of his intentions of proceeding on to St. Johns and keeping possession there. It appeared to me a wild, expensive, impracticable scheme…

What makes the letter particularly interesting, though, is that it doesn’t seem to be the only version that Arnold wrote. An alternate version (addressed to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety) is available in a compilation of Revolutionary War documents published in the 1830s-40s (text | page image). The letters are both dated May 19th, 1775, and are basically the same in content, but there are routinely differences in language, and occasionally major differences in content. Our draft of the letter, for instance, doesn’t include the following passage, which appears in the other version:

I wrote you, gentlemen, in my former letters, that I should be extremely glad to be superseded in my command here, as I find it next to impossible to repair the old fort at Ticonderoga, and am not qualified to direct in building a new one. I am really of opinion it will be necessary to employ one thousand or fifteen hundred men here this summer, in which I have the pleasure of being joined in sentiment by Mr. Romans, who is esteemed an able engineer….

… I beg leave to observe I have had intimations given me, that some persons had determined to apply to you and the Provincial Congress, to injure me in your esteem, by misrepresenting matters of fact. I know of no other motive they can have, only my refusing them commissions, for the very simple reason that I did not think them qualified. However, gentlemen, I have the satisfaction of imagining I am employed by gentlemen of so much candour, that my conduct will not be condemned until I have the opportunity of being heard.

It’s illuminating to note that these lines — which move beyond the immediate reporting of forts taken and cannons captured — were ones that Arnold seemed to hesitate to send.

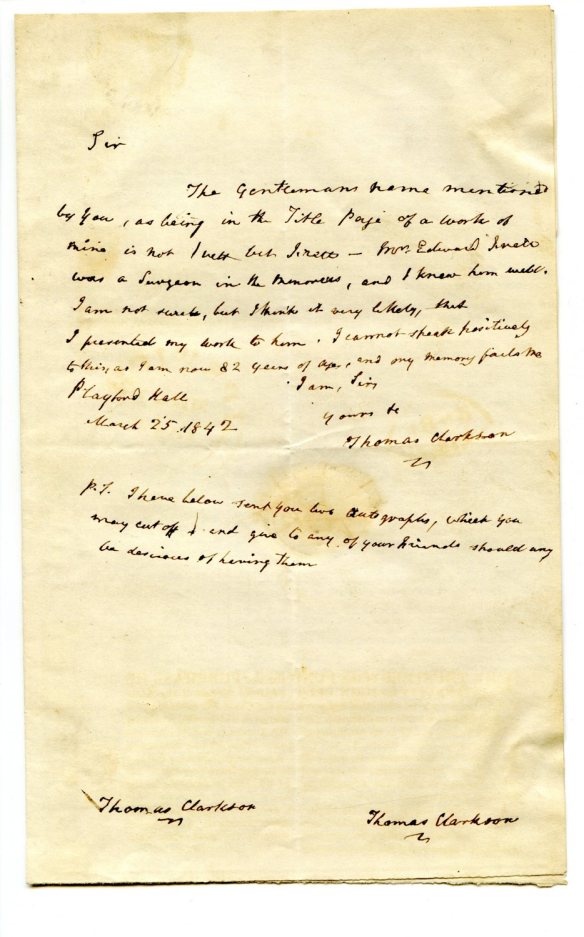

So why two copies, and why would they be different?* Unfortunately, our letter isn’t addressed, so we can only guess that it was intended for the same recipients (the MA Committee of Safety). But one bit of evidence appears in the last lines. Our copy concludes with this note:

For particulars [I] must refer you to Capt. Oswald, who has been very active and serviceable and is a prudent, good officer.

Indicating, it seems, that Oswald was delivering our copy of the letter. The other letter ends this way:

I must refer you for particulars to the bearer, Captain Jonathan Brown, who has been very active and serviceable, and is a prudent, good officer…

Scholars of the American Revolution (who are hopefully more knowledgeable of the conventions of military correspondence of the time) are encouraged to comment on whether Arnold was more likely to be sending two copies of a letter like this with different couriers, to ensure that it arrived safely, or sending a similar letter to two different sets of recipients.

In either case, it’s a reminder that even what seems like a clear piece of historical evidence might be only part of the story.

Here’s a transcription (spelling adjusted) of our copy of the letter:

Crown Point 19th May 1775

Gentlemen-

I wrote you the 14th instant by Mr. Romans, which I make no doubt you have received. The afternoon of the same day I left Ticonderoga with Capt. Brown and Arnold and fifty men in a small schooner. Arrived at Skenesborough and proceeded for St. Johns. The weather calm. 17th at 6 PM being within 30 miles of St. Johns. Manned out two small batteaux with 35 men and at 6 the next morning arrived there and surprised a sergeant and his party of 12 men and took the King’s sloop of about 70 tons and 2 brass six-pounders and 7 men without any loss on either side. The captain was hourly expected from Montreal with a large detachment of men, some guns and carriages for the sloop, as was a captain and 40 men from Chambly at 12 miles distance from St. Johns, so that providence seems to have smiled on us in arriving so fortunate an hour. For had we been 6 hours later in all probability we should have miscarried in our design. The wind proving favourable in two hours after our arrival we got on most all the stores, provisions and weighed anchor for this place with the sloop and 5 large batteaux, which we seized, having destroyed 5 others, and arrived here at 10 this morning, not leaving any one craft of any kind behind that the enemy can cross the lake in if they have any such intentions. I must here observe that in my return some distance this side [of] St. John I met Col. Allen with 90 or 100 of his men in a starving condition. I supplied him with provisions. He informed me of his intentions of proceeding on to St. Johns and keeping possession there. It appeared to me a wild, expensive, impracticable scheme and provided it could be carried into execution of no consequence so long as we are masters of the lake, [and] of that I make no doubt we should be as I am determined to arm the sloop and schooner immediately. For particulars [I] must refer you to Capt. Oswald, who has been very active and serviceable and is a prudent, good officer.

Bened: Arnold

Verso:

P.S. to the foregoing letter

By a return sent to Gen. Gage last week I find there are in the 7th and 26th regiments now in Canada 717 men including 170 we have taken prisoner. Enclosed is a list of cannon here at Ticonderoga:

[list follows]

—

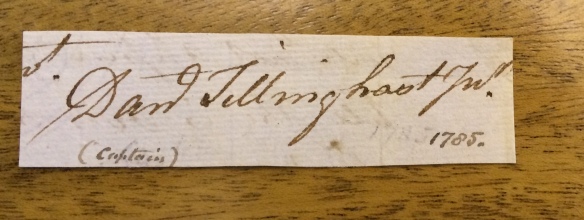

* It’s also possible, of course, that one or the other letters wasn’t actually composed by Arnold at all, or at least not on May 15th, 1775. Arnold seems to have signed his name in a number of ways, as evidenced by comparing this signature with this one, both dating from 1775. The latter version uses a two-story form of the “A” in “Arnold,” and seems similar in other ways. I haven’t seen a copy of the other letter, which may be part of the Library of Congress’s Peter Force Library, donated by the author of compilation in which that copy appears.